Written by Peter Reaburn | Planning Director | Cato Bolam Consultants

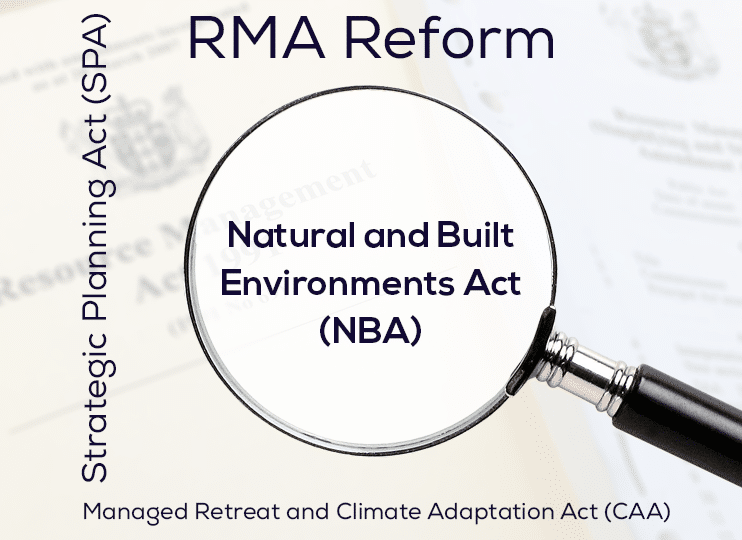

The initial public consultation round for the proposed Natural and Built Environments Act (NBA) is now underway, with public submissions on a recently released Draft to be considered by a Select Committee later this year. The intention is that new legislation will be in place by the end of 2022. The NBA is intended as the major piece of new law replacing the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA). The NBA will set environmental limits and set out expected outcomes. There will be important interactions between the NBA and spatial strategies developed under the new Strategic Planning Act (SPA). A separate Climate Adaptation Act (CAA) will deal with such issues as managed retreat.

While the NBA Draft is just an “exposure” document and there are major gaps and not a lot of detail, there is a lot in it that looks promising. This includes a refocussing of the RMA’s emphasis on responding to adverse effects to adding a list of positive outcomes for the environment that must be addressed in new national and regional plans. The NBA will also improve recognition of te ao Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi.

Many of Cato Bolam’s clients, and indeed many in society as a whole, will be looking at how the NBA will address the housing issue. The RMA has been widely criticised for imposing constraints on the ability of the housing sector to respond to housing demands, and for processes that take too long and cost too much.

One of the environmental outcomes that the Draft NBA says must be promoted is that housing supply is developed to provide choice to consumers, contribute to the affordability of housing, meet the diverse and changing needs of people and communities and support Māori housing aims. The ongoing provision of infrastructure services must also be promoted – an important recognition that lessening constraints on zoning for new development is not enough.

What this means in practice remains to be seen and is made less clear by the list of outcomes to be achieved being a mix of both environmental protection and allowing development. While it is an aim of the NBA to ensure that measures to avoid, remedy or mitigate effects do not place unreasonable costs on development this will be subject to compliance with environmental limits including in relation to air, biodiversity, coastal waters, estuaries, freshwater and soil. Most people will accept the importance of protecting our natural environment, although an additional layer of targets as well as limits would be preferable to see.

What is less certain is what will happen to the more subjective planning rules that are the cause of much of the debate and delays in getting housing projects underway. These are things like height and height in relation to boundary rules, open space, landscaping and building coverage requirements, yards, etc, and also urban design assessments. A lot of the angst experienced by developers lies in this area. The intention is that the NBA will lessen the emphasis on rules and assessments relating to subjective amenity values but that this will not be at the expense of quality urban design. What that may mean in terms of the detail is not at all clear.

Part of the answer may lie in the new National Planning Framework (NPF). The Minister for the Environment will be responsible for providing a set of mandatory national policies and standards, including natural environmental limits, outcomes and targets. We are a small country and there is clearly a lot of scope for removing complexity and inconsistency through having more national policies and standards. But the extent to which the NPF will get into detail, for instance on amenity matters, is not yet clear, nor – apart from a general guideline – what process will be used for putting the NPF in place. It is still possible that many of the issues that communities will be concerned about will be left to the new regional planning committees to sort out. The result could still look a lot like what we already have – perhaps even less flexibility if rigid standards are to be introduced. In which case a major aim of the new legislation will not have been achieved.

It is also not clear from the Draft NBA what will be done about the efficiency of planning processes. Many who have been involved with the RMA will say that inefficiency arises more from the culture and capability of local authorities and their planning departments than the legislation itself. This issue is not going to be assisted by new legislation that will inevitably introduce complexity and uncertainty and which, together with all the new plan requirements, will realistically take a long time to put in place. Over 100 existing plans will become 14, probably individually very large, new ones. There must be a major concern within local authorities about the capacity of existing structures and resources to deal with this and to carry on having to process plans and consents at the same time. In the least, different councils are going to have to look at how they coordinate resources. How this then relates to the complex issue of local government reform is a huge unknown in itself, although the Auckland super city experience should be looked at as there are a number of parallels with what is intended by this new legislation.

Watch this space!

Related news, RMA to be Replaced – Changes and impacts